The election of 1880 was shaping up to be the first time in history a President would be elected to a third term. Although Ulysses Grant finished his 2nd term in 1876 and was succeeded by Rutherford B. Hayes, Grant was still very popular and relatively young. As the Republican Convention began in the summer of 1880, Grant was the odds-on favorite to win the party nomination. When convention voting started, Grant received more votes than any other candidate, but could not attain the minimum number needed to win the nomination (50% of all delegates). An anti-Grant faction, still upset by financial scandals that occurred at the end of his administration, prevented him from attaining the needed majority. The voting continued for days with loyalties shifting around and some candidates dropping out. After 33 separate votes, Grant still couldn’t muster enough support for the nomination. Then a new Candidate was entered into the mix on the 34th vote. The state of Wisconsin moved 16 of their 18 votes (all previously for Grant) to James Garfield, who up to that point was not even a candidate. Garfield was a Congressman from the state of Ohio who had come to the convention to deliver the nominating speech for candidate (and US Senator) John Sherman of Ohio. This was the first indication of an abandonment of Grant. Combined with a great desire to break what was seen as a hopeless stalemate, other states also began moving some or all of their votes to Garfield. On the 36th vote Garfield received a majority and officially became the Republican nominee for the 1880 election. Five months later, Garfield went on to win the general election. On March 4th, 1881 he was inaugurated the 20th President of the United States.

On July 2nd, 1881, four months after his inauguration, Garfield decided to join his wife and children at the New Jersey shore for a summer vacation. He left the White House that day with a group of others for the 6th street station of the Baltimore and Potomac railroad. Waiting for him at the train station was a disturbed man named Charles Guiteau who had recently been denied a government job as Minister to France. Less than a year earlier, Guiteau had been on a “steamer” boat that crashed into another boat in the middle of the night on Long Island Sound. The resulting fiery explosion killed thirty people. Guiteau was one of the lucky survivors.

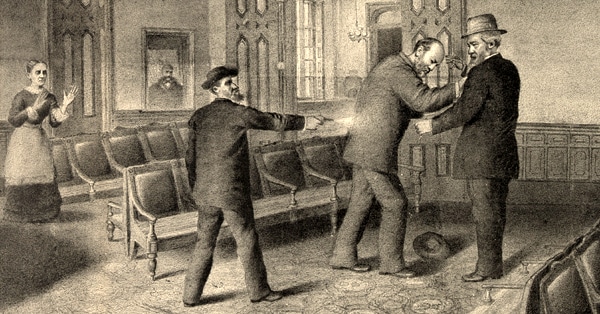

While waiting for the train to arrive, Garfield was approached and shot twice by Guiteau. The first bullet grazed Garfield’s arm and passed through his clothing. The second entered his back, broke two ribs, and lodged in his abdomen. In a twist of fate, one of the first people by his side was Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, the former President’s son.¹ Lincoln immediately had his carriage sent to retrieve Dr. D. Willard Bliss. Bliss was one of the doctors who tried to save President Lincoln after he was shot sixteen years earlier. Bliss was also was a longtime acquaintance of Garfield. Interestingly, the initial “D” in Dr. Bliss’s name stands for “Doctor”, his real first name given to him by his parents at birth. Garfield was made as comfortable as possible on the train station floor until doctors arrived. Dr. Charles Purvis was one of the first doctors to come into the station. Among his many other honors², Purvis now had the distinction of being the first black doctor ever to treat a U.S. President. Within the first hour, a total of nine doctors descended on the scene, with Dr. Bliss taking the lead role. At least three of these men, Dr. Bliss among them, inserted their unsterilized fingers and metal probes into the wound to try and find the bullet.

Up to this point in history, the choice of Vice President (running mate) was not made by the Presidential candidate. The convention-goers for each party voted separately for who they wanted as Vice President, irrespective of the wishes of the primary candidate. Their choice was usually made to lure voters from states where the Presidential candidate wasn’t as popular. Sometimes this resulted in a Vice President with a dissimilar ideological mind from his boss. Chester A. Arthur was the chosen Vice President for Garfield, mainly because of Arthur’s pull with New York voters. Arthur was a big proponent of (and participant in) the “patronage” system for government jobs and influence, a practice that Garfield was targeting for major reform. The two did not see eye-to-eye on this topic. Arthur was in New York at the time Garfield was shot and decided to remain there. He and his advisers feared that because of their fierce disagreement over the patronage system, Arthur might somehow be seen as complicit in the attack on Garfield if he rushed back to Washington too quickly to “take over”.

Doctors in the US at the time had not yet bought into the new theory of anti-sepsis as trumpeted in recent years by British surgeon Joseph Lister. Lister had been evangelizing a theory put forth by Luis Pasteur that microscopic organisms (germs) were causing infections at wound sites. These germs needed to be neutralized, or at least kept at bay, by sterilizing the wound along with all the medical instruments, surgeon’s hands, and surrounding environment of the patient. Doctors in Europe were convinced of Lister’s theories and had already begun using sterilization protocols in all their procedures. Post-surgical death rates there had already begun to plummet as a result. Not so in the US. It wouldn’t be until the 1890’s that antiseptic protocols in surgery came into regular use in this country. Thus, doctors probed the wound with germ-infested tools and fingers to try and locate the bullet in Garfield’s gut.³

Garfield was weak, but stable enough to be transported the short distance from the train station back to the White House. There, an upper floor room was setup as a makeshift hospital. Everything possible was done to make Garfield more comfortable. Being the middle of summer, the temperatures were sweltering. In an attempt to combat the heat, a core of engineers from the US Navy brought in a contraption that combined blocks of ice, tubes, and fans to cool the air in Garfield’s room. After some trial and error, the country’s first air conditioner brought down the temperature in the room by 20 degrees. The doctors were not having any luck locating the bullet in Garfield’s abdomen. Every succeeding attempt to probe for it was more painful to the patient. They knew his survival likely hinged on surgically removing the bullet, which they dared not try without knowing precisely where it was. They then received a letter from an inventor claiming to have a possible solution.

Alexander Graham Bell had just invented the telephone 5 years earlier. The awesome significance of this invention, and Bell’s extraordinary place in history, were not yet known. He was a big fan of President Garfield. Bell believed there was a way to “detect” a metal object within the body using electricity, without needing to invasively probe the wound (X-Ray technology wouldn’t be invented for 14 more years). Upon hearing of Garfield’s condition, he worked tirelessly in his lab to turn his idea into a tool. His first attempt was an ungainly contrivance of wires and magnets that would supposedly produce a sound through a speaker (borrowed from one of his telephones) when a metal object was in close proximity to an electrified probe. The probe had a sensitivity of about 2 inches and could work outside the body. He convinced Garfield’s doctors to let him bring it to the White House and use it on the President. However, as is often the case, what worked in the lab did not produce the same results in the field. Two things worked against Bell that day:

- Bliss, Garfield’s primary physician, insisted on operating the device himself even though he was unfamiliar with it and not nearly as practiced as Bell. In addition, Bliss only scanned the area on Garfield’s right side where he had previously told everyone the bullet must be. He did not try scanning any other area.

- In his rush to re-assemble his invention at the White House after having to break it down for transportation from his lab, Bell forgot to connect an important component, greatly reducing the sensitivity of the device. He only discovered his mistake the next day after returning to his lab.

Over the next several days, Bell made some modifications and greatly improved the sensitivity of his device. It now had a five-inch range, more than twice that of his first version. To test it in a more realistic scenario, he wanted a human subject with a metal object somewhere in his body. As it turned out, this was not that difficult since there were hundreds of surviving Civil War veterans walking around in good health with shrapnel and bullets encased within them. Bell tested his improved device on one of these veterans and precisely located the metal object inside him.

Back at the White House for his 2nd attempt, Bell was stymied once again. This time however, it was not because his metal detector wasn’t working. Bell was unaware of the metal springs present in a new kind of mattress recently installed under the soft horsehair mattress upon which Garfield was lying. Intended to make the President more comfortable, this box spring mattress – which wouldn’t become popular for 20 more years – was interfering with Bell’s metal detector. In addition, Garfield’s doctors had hardened in their belief that the bullet had lodged itself on the right side of Garfield’s abdomen, a short distance from where it entered the body. While Doctor Bliss did allow Bell to operate the detector this time, Bell was not permitted to place the probe anywhere other than the right side of Garfield’s abdomen. Bliss and the other doctors knew that if Bell located the bullet far away from where they thought it was (it had actually traveled much further and was on Garfield’s left side), their professional judgement and reputation would be called into question. Given that this was the highest profile case of their respective careers, they did not want to risk being undermined by an inventor who was not even a doctor. Bell did believe he heard a faint sound from his device as it was moved closer to the left edge of his allowed examination area. But Dr. Bliss simply took this as confirmation of his earlier assessment that the bullet was on the right side, just deeper. Bell, however, was not convinced. The sound was very faint and was also affected by the false returns from the box spring mattress. In the end, Bell’s attempt to find the bullet was considered inconclusive.

Garfield was given nourishment and wound care in the hopes that he could now survive with the bullet remaining inside him. After all, it was known this was possible from the experience of Civil War veterans as mentioned earlier. However, what the doctors didn’t know was that infection was rapidly spreading and sepsis had set in throughout Garfield’s body. In a last desperate attempt to save him, his Doctors decided to move Garfield to a seaside residence in New Jersey to be exposed to the fresh and rejuvenating ocean air. He lingered on for two weeks before finally succumbing at 10:35 PM on September 18th, 1881. After surviving for more than 12 weeks, the consensus was that Garfield died from sepsis.

While Chester Arthur did pay a short visit to Garfield in his sickbed at the White House, he was back in New York at the time of Garfield’s death. Four hours after Garfield’s passing, New York Supreme Court Judge John R. Brady administered the oath of office to Arthur at 2:30AM in Arthur’s brownstone home on Lexington avenue. Arthur became the first of three Vice Presidents to be sworn into the country’s highest office while outside of the nation’s capitol. The other two were Theodore Roosevelt (in New York following President McKinley’s assassination) and Lyndon Johnson (in Dallas following President Kennedy’s assassination).

James Garfield was unlucky enough to be just on the cusp of significant turning points in medical and technological advancement. Had his doctors used Joseph Lister’s antiseptic protocol, Garfield might have survived. Alexander Graham Bell’s hastily constructed device for locating the bullet went on to become the accepted design for all future metal detectors. Had Bell been able to use it on the left side of Garfield’s abdomen, the bullet might have been found and could possibly have been surgically removed.

The 12 weeks between the day the bullet entered Garfield’s body and his eventual death were among the most fascinating in our history on a number of fronts. James Garfield’s story was remarkable even though he was only President for little more than six months.

1As fate would have it, 20 years later Robert Todd Lincoln would be present just outside the building where President William McKinley was assassinated. He is the only person in history known to be in such close proximity to three Presidential assassinations.

2Dr. Purvis was one of only a handful of black surgeons in the Civil War. He was not only one of the first black men to attend an American medical school, but also one of the founders and faculty members of Howard University Medical School. He was the first black person to be a member of the D.C. board of Medical Examiners.

3The infection, seeded by wound probing at the train station as well as many more subsequent invasive attempts to find the bullet, was most likely the proximate cause of Garfield’s eventual death. An autopsy later revealed the bullet never hit any of his vital organs.

2 Responses

Fascinating account of events. Garfield’s family should have sued someone for wrongful death, right? Apparently people at that time (not that long ago) were satisfied with their healthcare. And to think, with all the amazing technology and medications we have today, people complain that we have to improve the quality of our healthcare.

Not only were they satisfied with their healthcare, everyone acted as their own “FDA” in the decision to try a new drug or procedure. The Food and Drug Administration as we know it today wasn’t formed until 25 years after Garfield’s death (1906). Most of Bell’s “human trials” with his metal detector were done on Garfield himself (the patient).

Also, I love the very clear-eyed references and legal reasoning in use at that time. Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, tried to use the insanity defense to avoid punishment after Garfield died. Had he been found insane, he would’ve been remanded to a “Lunatic Asylum”. But common sense prevailed and he was found guilty and hung in public. No long appeals, last-minute stays, or pardon. His execution was even celebrated, with pieces of the hanging rope sold as souvenirs. The good old days…