From the moment of our current President’s inauguration, his foes have entertained the notion of impeachment. But with the President’s party controlling both houses of Congress, this was little more than fanciful thought. However, at the start of 2019 Democrats will take control of the house of Representatives and the possibility of impeachment proceedings, while still improbable, are now possible.

At this point it is unclear precisely what offense a Trump impeachment would be based on, as the cry for it has been driven much more by disgust with his personal style and manner as opposed to hard evidence of any “high crime or misdemeanor”.

To put in context the difficulty of achieving a Presidential impeachment, there have only been two successful cases¹ in the entire 231-year history of the United States. Neither of these cases resulted in the removal of the President from office (by the Senate) as the “crimes” committed were not deemed severe enough. Both these cases were politically motivated, originating from an intense dislike of the behavior and style of the person holding the office. In each circumstance, a “trap” of sorts had to be laid by the President’s opponents to try and ensnare him in enough legal jeopardy to technically justify impeachment.

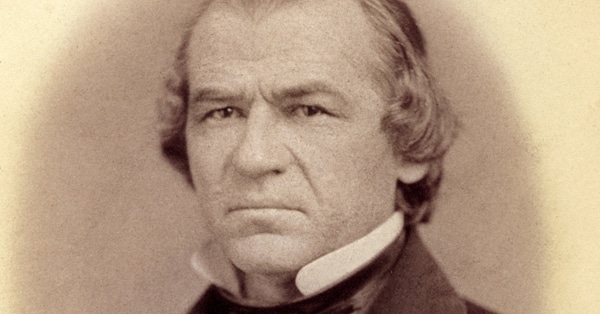

The first case was in 1868 against President Andrew Johnson (the photo for this post). Johnson was never actually elected to the Presidency. He was Vice President in 1865 when President Lincoln was assassinated. Thus, Johnson became President by way of succession. At the time Johnson assumed the Presidency, the Civil War had just ended and there was an ongoing debate as to the best way forward to “Reconstruct” the south. Lincoln believed it was the President’s duty to set and govern the Reconstruction plan. However, Congress had their own ideas and believed they should have a role in defining the plan as well, if not the entire responsibility for Reconstruction. This dispute continued after Johnson took office and became far more acrimonious than it ever had been under Lincoln. The increasing rancor was mostly due to Johnson’s intransigence and refusal to compromise on how the seceded southern states should be re-admitted into the Union. Ultimately, Johnson’s detractors wanted him removed from office believing he was causing irreparable harm to the Reconstruction effort. But apart from being impolitic, stubborn and unyielding in his views, Johnson hadn’t done anything illegal to justify removing him from office. So, Congress laid a trap. Johnson disliked his Secretary of War Edward Stanton and believed he was becoming more and more disloyal and unsupportive of Administration policies. Suspecting Johnson might try to fire Stanton, Congress passed a law² prohibiting the President from firing any official who had been confirmed by the Senate, without Congress first “approving” the removal. Johnson of course vetoed the bill, but Congress then overrode his veto, preventing Johnson from firing Stanton.³ After trying unsuccessfully to exploit a loophole in the new law, a frustrated Johnson ultimately fired Stanton without Senate approval and created the legal basis for impeachment by “breaking” the new law. In his subsequent trial in the Senate, not every Senator was convinced that the new law Johnson broke was constitutional in the first place, and even if it was, violating it didn’t rise to the level of removal from office. Johnson ended up being acquitted by 1 vote and remained in office for the rest of his term. The law he was accused of breaking was subsequently repealed by Congress in 1887 and later determined to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

The other case occurred exactly 130 years later against President Bill Clinton. Clinton has the distinction of being the only elected President in history to be impeached. While the details of the Clinton case differ dramatically from Johnson’s case, the politics involved are very similar. Clinton’s opponents had become increasingly irritated with the personal behavior of the President. At the time, he was being investigated for possible wrongdoing in a past real estate deal known as “Whitewater”. But it was his sexual relationship with a young White House intern, combined with constant reminders of his past extramarital escapades, that his critics believed were sullying the office of the President. Despite their professed “disgust” with Clinton’s promiscuity, there was nothing illegal about it and it did not represent grounds for impeachment. So, much like with Johnson, a trap was laid. Playing off what they hoped would be too embarrassing an admission for the President, the Whitewater prosecutor asked Clinton, while under oath, if he had sexual relations with a White House intern. When Clinton answered “no” he fell directly into a perjury trap. Since there was eyewitness testimony to the relationship (the intern) and physical evidence of their activity (her stained dress), there was now a legal basis for impeachment because the President committed perjury by lying under oath. Just as in Johnson’s case, the Senate voted to acquit Clinton, albeit by a greater margin than just 1 vote. The “crime”, and how it came to be committed, simply did not warrant removal from office. Like Johnson, Clinton finished out his term.

The current political climate surrounding President Trump is eerily similar to both these prior cases. Those opposed to the President, including members of his own party, are intensely frustrated with his behavior, style and comportment as President and want him removed. However, much as with Johnson and Clinton, he has not committed any prosecutable “crime” that could be used as the basis for impeachment. His partisan critics have accused him of many wrongdoings including flights into the truly fanciful, but there is a lack of the hard evidence and/or witnesses that ultimately accompanied the successful impeachment cases of both Johnson and Clinton. However, Trump’s volatile personality and propensity to react quickly to events, make him susceptible to a cleverly-laid legal trap such as ensnared both Johnson and Clinton. The odds of this occurring will increase dramatically when his opponents take control of the House of Representatives next month. The forthcoming release of the Mueller report will raise those odds even further. Trump will need to be carefully watchful and impose some self-discipline. History is on his side though, and the odds of him being the first President in 231 years to be removed from office by way of impeachment are exceedingly low.

¹ It is often mentioned that President Nixon was impeached after the Watergate scandal in 1974. While the House Judiciary Committee did approve Articles of Impeachment against Nixon, the full House of Representatives never voted on those articles before Nixon resigned. Nixon was not impeached.

² The official name of this 1867 law was the “Tenure of Office Act”. The loophole in the law that Johnson tried to exploit (before firing Stanton) was that it allowed for the President to “suspend” a Senate confirmed official while Congress was adjourned. Upon Congresses return, the President would then have to justify the suspension which could result in the original occupant being re-instated if the reasons were not satisfactory. Johnson did in fact suspend Stanton just 15 days after Congress adjourned in August of 1867 and named General Ulysses S. Grant as the acting Secretary of War. Upon Congress’s return Johnson presented his list of reasons justifying the suspension of Stanton as required by the new law. When Congress did not accept Johnson’s justification, Johnson proceeded to fire Stanton anyway and the impeachment “trap” was sprung.

³ Ironically, the 1867 “Tenure of Office Act” has a striking resemblance to a current bill before the US Senate fashioned to prevent special prosecutor Robert Mueller from being fired by the President (H.R. 5476, The Special Counsel Independence and Integrity Act). This bill states that a Judge, not Congress, would be able to decide if the reasons for dismissal were valid and if not, the fired Special Prosecutor would be re-instated. History attempting to repeat itself? Thus far, the Senate has refused to vote on this bill preventing it from moving forward. Even if it did, it would likely face a Presidential veto.